Monolith. Regardless of the Millers @ Yale Union

Willem Oorebeek’s exhibition Monolith. Regardless of the Millers feels a little bit like walking into the middle of a conversation. His current retrospective at Yale Union continues his practice of showing and reconfiguring the same images that have populated his installations for decades, ordering and reordering, adding and subtracting along the way. While this might not sound like a recipe for fresh or timely work, an innovative use of architecture makes Oorebeek’s first solo exhibition in the US a particularly interesting place to pick up the artist’s narrative.

YU does not have a reputation for accessibility. Gallery hours have been limited, little interaction has been made with local artists, and the website is aggressively opaque. In fairness, the organization is working to address some of these challenges, while it seems determined to wear others as a badge of honor. What YU does have, however, is a stunningly beautiful barn of an exhibition space.

Flooded with natural light, it is perfect for large-scale sculptures, but presents multiple challenges to showing two-dimensional work like Oorebeek’s. To address these difficulties, YU and Oorebeek collaborated with Kris Kimpe, an architect from Antwerp, to transform the gallery into a labyrinth of corridors constructed of raw wood and intermittently hung drywall. This strategy places the works in a linear trajectory, revealing itself to viewers in a series of sections, but never as a whole. It’s an ambitious endeavor and reminds me why I will always love exhibitions more than I will ever love any individual artwork.

In one of the maze’s many corridors are groupings of black ink prints on black backgrounds. Called BLACKOUTS, the images are so subtle they are virtually impossible to capture on camera and can only be viewed from a few inches from the surface. Around a different corner are large scale printings of patterns that have a wallpaper effect in their installation. It’s in creating breathing room for these disparate bodies of work that Kimpe’s architectural vision really shines. It creates connections and divisions that reward repeated viewings.

The most interesting of these connections is between two groupings near the beginning of the exhibition. Starting at the entrance, the viewer is presented with a series of wall-mounted semi-reflective surfaces installed over textured rubber floor tiles. These works mirror the full body of the viewer, only distorted and pixelated. The experience is a visual reference to a series of works encountered in another corridor: life sized black and white figures enlarged from commercial printing, the dots of the images amplified by their size.

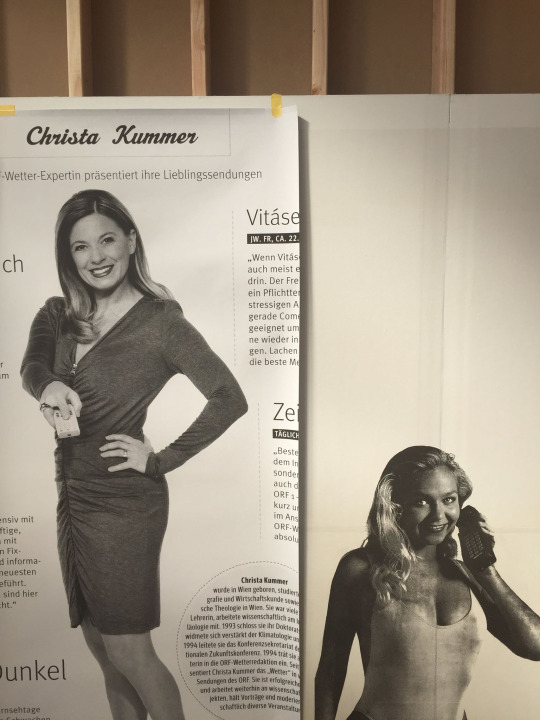

Willem Oorebeek, Vertical Club installation via

These isolated figures are part of an ongoing series that Oorebeek calls Vertical Club. At first, they are laid out on their own and then later the images are overlapped with text from his recent book project Vertical Klub. These works, which again have been shown by Oorebeek in almost the same format for decades, take on a very different meaning in the digital age. What once would have been seen as banal and everyday, now seems unavoidably nostalgic in the wake of print media’s increasing obsolescence. This nostalgic preciousness is amplified by the fact that Oorebeek only prints a limited edition of each figure. Members of the Vertical Club are pasted directly on to the wall and are destroyed during the de-installation process, creating a self-imposed scarcity for each figure.

On one level Monolith. Regardless of the Millers can be viewed as an exploration of print techniques. It speaks to the manipulation of visual language through copy and repetition, and how everyday images can be unmoored from their original contexts and presented for new consideration. Oorebeek uses a rich collection of sources including advertisements, images of Chinese communist heroes, magazines, A reference to La Femme 100 Têtes (100 Women Without Heads) by Max Ernst, Sigmund Freud’s couch, and Roy Lichtenstein to name a few.

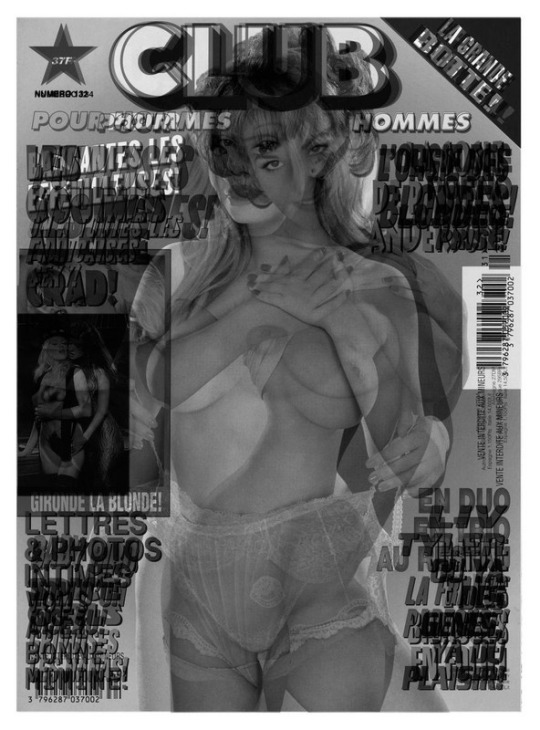

Willem Oorebeek, More CLUB, 2010

There are also a lot of images of women. And just as pictures of women in the media are highly loaded, so too are they in Monolith. Regardless of the Millers. It is interesting to note that this show opened just as Hank Willis Thomas’ Unbranded: A Century of White Women, 1915-2015 closed at Jack Shainman Gallery in New York. Thomas also uses found images, submitting them to what he calls an “unbranding technique,“ removing the copy and leaving behind only the visual signifiers and his own veiled titles.

What Unbranded: A Century of White Women points to directly (the often problematic presentation of women’s bodies in media) hangs more ambiguously in Oorebeek’s installation. No amount of repetition can scrub away the blatant offers of pleasure and consumption presented in these images, and it’s not clear if Oorebeek’s work is capable of addressing those issues in any meaningful way.

Hank Willis Thomas, Haters gon’ hate, 1960/2015. Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

But it’s hard to tell. The male gaze is still the default position in our culture and so it makes sense that it also exists as the expected perspective in many forms of visual communication. Yet this perspective can often be an uncomfortable fit with viewers like myself. One of the requirements of the Vertical Club subjects is that the figure is looking into the camera, gazing back at the viewer. At the beginning of this exhibition I got to see myself as a member of this club in the reflective entrance pieces. I saw myself straight on, looking into my own eyes, not coyly turned or styled, but self possessed. It’s an image that doesn’t exist for the rest of the women shown in Oorebeek’s exhibition, which reveals a lot about the the artist’s curatorial choices.

Willem Oorebeek, Image from YU exhibition. Top text translation: “Hardly a member and we already see the difference.”

Despite this, it’s hard to deny the formalistic pleasures, attention to detail, and ambitious scope of Monolith. Regardless of the Millers. The old-school, semiotic critique of mass imagery is turned into a love story. One in which a printer, with ink stained hands, will continue to print black on black on black, until the images are unrecognizable and the equipment becomes impossible to repair. Even then, an Oorebeek exhibition will still be like walking into the middle of a conversation.

The show is open May 30–July 19

Thursday–Sunday, 2–5pm for more info visit yaleunion.org