Melanie Stevens: in medias res(t) at Stumptown

Melanie Stevens’ latest exhibition in medias res(t) appropriates images, meme structures and colloquial internet based language to interrogate the contemporary non-stop consumption of media and the role of the Black body in that media. It is appropriate then that the exhibition is displayed in Stumptown Coffee’s high volume 3rd Street storefront in Downtown Portland where visitors are typically found planted in front of laptops and smartphones. In medias res(t) is the third exhibition supported by Stumptown’s Artist Fellowship. I sincerely applaud Stumptown’s Fellowship curator May Barruel for so far wielding this fellowship to exhibit underrepresented artists. However, I am nervous that Stumptown’s commercial setting applies a matrix of commodification and commercialism that brought particular tension to Stevens’ exhibition visualizing exhausted Black figures among that day’s nearly all white staff and clientele. In medias res(t) is activated by this tension; Stevens smartly deploys familiar formal choices critically carving survival spaces within the white-supremacist (world and) mediascape.

In medias res(t) features two pieces, one enormous “scrolling patchwork” textile banner spanning over 70 feet along the coffee shop’s main wall, and a triptych print series.

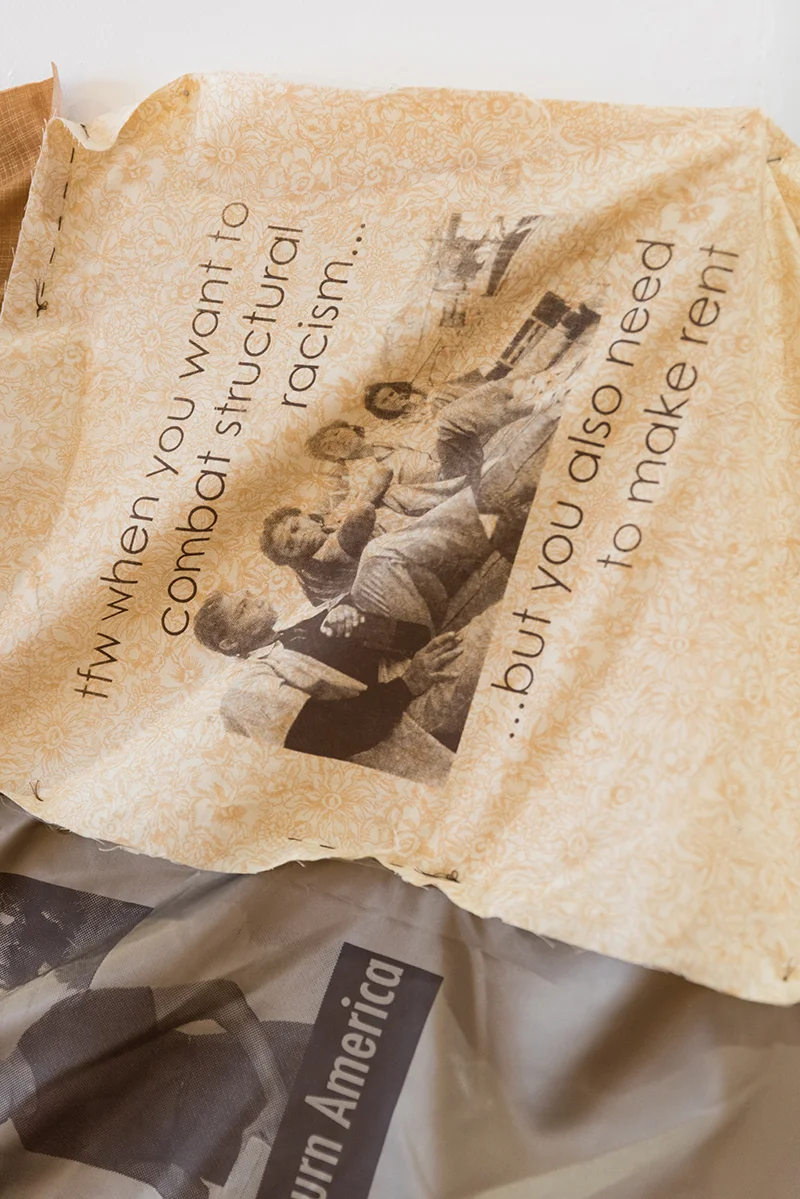

The scrolling patchwork is an ongoing project involving muslin and polyester panels hand stitched together into a massive and delicate banner which loops and dips in dramatic scallops dominating the entire long wall of the coffee shop. The fabrics range in skin tones from cream and beige to sepia and umber. Some patches resemble aged bedding with faint paisley or floral prints. Those sides of the fabric which are not stitched together are left raw so that shredded edges of varying lengths hang loosely, drifting in the breeze of the central cooling and coffee shop guest’s movements. The entire piece stretches up and loops over curtain rods installed about twenty feet up the walls draping dramatically in 10-20 foot parabolas, gently folding to obscure printed imagery requiring viewer’s proximity for legibility.

Approximately half of the textile panels include prints of illustrated comics or aggregated screenshots from news shows paired with casual and loaded text like “Tfw you want to combat structural racism... but you also need to make rent…” Stevens zeroes in on the coping ambivalence of audiences playfully disidentifying with mass media dissemination and consumption. These images appear in the format of ready-to-consume memes but Stevens’ colossal concepts of structural racism and self censorship refuse to be so easily swallowed. This work is described as a “scrolling patchwork” calling imagery of a night curled up in bed and swiping through the unending stream of the feed. These days, that includes unique individual’s stories of untimely death at the hands of police officers and entitled me. The volume of stories and subsequent images flattens experiences to a generic categories of violence breeding desensitization in the regular viewer. Stevens has woven together the most familiar cultural and physical fabrics of our lives into an entirely unsettling patchwork.

This cycle of never-ending violence and the continued exasperation or misunderstanding by dominant groups builds an ouroboros between the exposure of past violence and in anticipation of the inevitable future violence. Thus questioning how media coverage is consumed and digested is paramount.

Where Stevens’ banner depicts moments of internal conflict, humor, and resonance, her triptych focuses on televised moments of public exasperation and composure of prominent Black figures. The central image of the triptych (a popular one in Stevens’ oeuvre) features James Baldwin in a televised interview with his eyes closed, leaning his forehead against his outstretched fingers. His brow is furrowed in complex lines of grief, exhaustion, and forced composure. Above the iconic, vulnerable image is the caption “MOOD:” The entire image is printed in a newsprint dot structure which breaks down as on top of a busy woodgrain pattern. The camera spectacularized Baldwin’s sincerity. Stevens camouflages the tender image of Baldwin with pattern, rendering, and caption. In this small abstraction, Stevens protects Baldwin in his vulnerability, though the pop style print overlayed on the over rendered wood print playfully pointing to overt signifiers of style.

It is uncanny that the beige, brown, black and white motif of In medias res(t) matches the bright white painted walls, beige leather couches and unfinished wooden tables of Stumptown Coffee. In Stevens’ work, this color palette is humanized in reference to bedding and corporeal tones, but in the coffee shop these colors industrial and decidedly neutral, pointing to organic but never human elements.

Melanie Stevens is the third recipient of the Stumptown Artist Fellowship receiving $2,000 and a six to eight week exhibition, including a catered opening reception, in the highly trafficked 3rd Street Stumptown location. The project is headed by May Barruel who has curated work at the 3rd Street Stumptown since 2007 and owns and operates Nationale gallery in Portland. Barruel previously selected Wendy Red Star and Jennifer Brommer for the Fellowship who, along with Stevens, are Portland-based artists pressurizing historical and contemporary visual narratives of women and minorities through primarily figural artwork.

In her first interview about the artist fellowship, Barruel was asked to explain the difference between curating for Stumptown and her own gallery. Barruel describes wanting “to be a lot more conscious of what our customers and staff might want to see” explaining that large work that engages the space and brightly colored work that combats the dreary weather are the most successful features.

But the three exhibitions of the Fellowship have all included figural work depicting Native American women, the very rich and elderly in the South, and now Black figures in front of an expecting public. Barruel has tapped into an additional altruistic desire from the public, to see and elevate artwork from underrepresented artists producing incisive, politicized artwork. But considering Barruel’s curatorial criteria in a capitalist setting, I wonder why exactly does the staff and clientele want to see this work? Do audiences want to see large artworks featuring Black figures in their coffee shop because they resonate with Stevens’ goals of interrogating violent media? Or, do audiences want to see large artworks featuring Black figures in their coffee shop because it fulfills a desire for superficial diverse visibility?

The Artist Fellowship is structurally complex because it both grants opportunity, financial support, and visibility to talented and critical local artists in a town where exhibition and financial resources continue to shrink and Stumptown capitalizes on the the social currency of support and inclusion. In this instance, in medias res(t) harnesses both offerings as an opportunity to illustrate the tension of production and consumption.

The potency of Stevens’ pairings of publicly exasperated Black figures in this stark coffee shop coalesces when the white baristas abruptly change the music to Kanye West’s “My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy.” Too confidently speakers blare the n word, and I am hyper aware of the all white clientele and my own white body in this highly curated space. From behind the marble counter, the baristas appear unaffected as Yeezy croons about the violence of Chicago threatening classrooms and the lure of addictive coping mechanisms. I want to laugh both with discomfort and with recognition that this space is manifesting the very same uncomfortable-recognition-this-is-problematic-but-what-can-I-do tone that Stevens’ invokes with, “TFW you want to combat structural racism... but you also need to make rent…”

Stevens’ work is in exactly the right setting to question the normalization of depictions of violence and the tragic exhaustion of Black folks in the media. Looking around me now, every single person is interacting with phones, laptops, or cameras, as they are surrounded by Stevens’ ambivalent history of representation and public vulnerability. Each coffee drinker is in their private realm, together, in public. Each person is most certainly scrolling by a published or personal account of oppression. Each person is implicated in this structure together but experiencing it (or not) privately. Some of us just are trying to show meaningful artwork. Some of us are just trying to get a cup of coffee. Some of us are just trying to make rent.

in medias res(t) is on view through May 16, 2018.

Photos by Mario Gallucci. Courtesy of the artist and Stumptown Coffee Roasters.