Mike Bray at Fourteen30 Contemporary: light grammar/grammar light

The all-white floors, walls, and ceilings of Fourteen30accentuate the strong ties to minimalism in five new pieces by Eugene-based artist Mike Bray. Bray pulls materials and methods from minimalism of the 1960’s and 1970’s at every possible opportunity. Mirrors, neon, gridded compositions, ready-made elements, industrial materials, clean lines and undisguised materiality all contribute to the feeling that these works could belong at Dia:Beacon. Bray does present his own unique spin on this established aesthetic: where the minimalists utilized industrial materials in art, Bray takes the same approach with the film industry by appropriating tools used in movie-making and referencing sets and production methods. In stark contrast to cinema, however, Bray gives the viewer no narrative context through which to grasp the work.

The sculpture in the front room, Day for Night, uses four production light stands to hold up wood and metal replicas of circular light scrims, which filter artificial lighting on movie sets. Like most of the pieces in the show, the work contains references to utilitarian objects that are indecipherable to anyone who hasn’t worked in movie production. Because of this opacity, the value of bringing the objects hidden out-of-frame in cinema to our attention in the gallery risks being lost in translation to the untrained viewer. However, there is still a certain formal charm and humor in the cluster of lanky, awkward objects in Day for Night even as the story behind them remains obscured.

Mike Bray, Intersect Theory, 2016

Mike Bray, The necessity to interfere with movement (detail), 2016

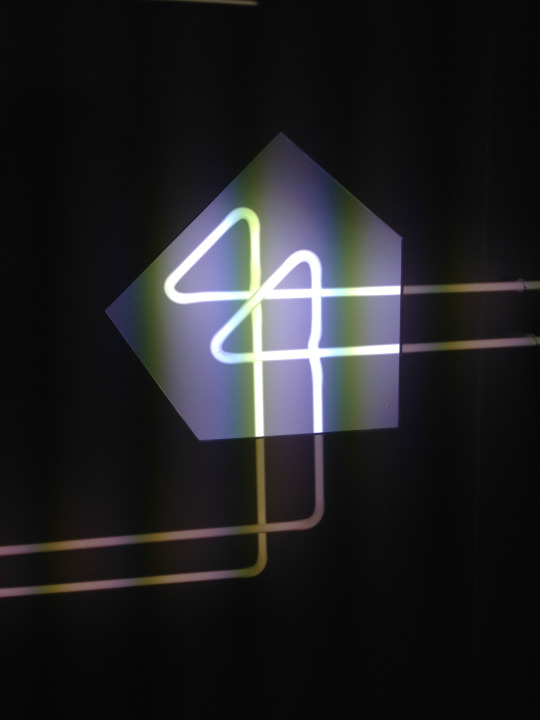

Transparency and reflectivity are found throughout the exhibition. The overlapping translucent effect of the mesh screens in Day for Night is replicated in Intersect Theory, a sculpture of intersecting two-way mirrors, and The necessity to interfere with movement in the next room. These two sculptural works and the prism featured in Bray’s video Angles of Refraction experiment with light as it’s own material–not a new concept, but potent when applied to the context of cinema as a system of modifying and commodifying light.

Mike Bray, Angles of Refraction, 2016

The video features a hand picking up, turning, and putting down a prism –this prism itself was presented as a sculpture in an earlier exhibition of Bray’s work at Fourteen30. Taking choreography from a Muybridge motion study of a hand picking up a baseball, the 22-second video feels more like an infomercial than a study. The high-definition manicured hand and glossy surface tells us the object is desirable, but not why.

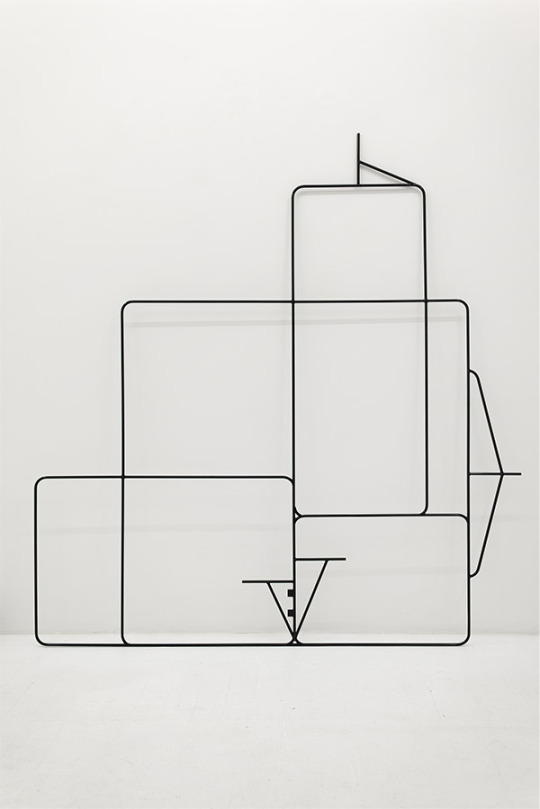

Blocking out the Sun, composed of steel rods welded in a flat asymmetrical grid (which would, in fact, block hardly any sun at all) also uses minimalist elements of gridded compositions and sculptural two-dimensional compositions. In the context of film, it likely references and combines standard dimensions of another obscure film industry tool: light cutters – used to control light on a movie set. Or it might simply be a pleasing arrangement of welded, powder-coated steel rod leaned against the gallery wall.

Mike Bray, Blocking out the sun, 2016

Viewers curious to engage with the work at a deeper level are certainly left to fend for themselves without any didactic information to accompany the work. Only obtuse titles, dimensions, and materials give any additional hints as to the conceptual ethos of the pieces.

This lack of information seems to work against the power of cinema, which comes in part from the ability of narratives to transform ordinary objects into extraordinary objects. The absence of any language or story around Bray’s pieces, in the pure-white gallery space could come across as intimidating. The exhibition constantly alludes to a conceptual complexity that seems out of reach. Maybe our attachment to narrative, readily fulfilled by the film industry, is exactly what Bray is attempting to highlight with its absence. There is some pleasure in surrendering yourself to the formalist observation that Bray’s pieces invite, but overall the exhibition left me craving more access points to conceptual engagement.

Bray’s light grammar / grammar light is on at Fourteen 30 Contemporary til March 5, 2016.

Images courtesy of Fourteen 30 Contemporary and Taryn Wiens